Tawayafs, often called baijis, are the singing and dancing women who used to occupy center-stage in the performing arts of India. Here we will see mujhras, courtesan performances by Madhuri Devi (Calcutta), Rani Singh (Mirzapur), Lakshmi Bai (Banaras) and Baby (Calcutta). I felt priviledged to attend these events. Sadly the tradition is nearly totally deceased. In the words of Ustad Abdul Latif Khan: "these women kept our music alive for the last four hundred years". But the tradition has been ravaged, beginning in the late nineteenth century by:

1) Victorian moral values, imported on a large scale by a lower class of British soldiers and civil servants and their families who began to populate India after the opening of the Suez Canal;

2) a large number of repressive ordinances, meant to curb vice and prostitution, brought in by both the colonial government and its native successor;

3) embassassment among middle-class musicians about the actual history of Indian music and a virulent movement towards covering up and disassociating from this history. As women who were not from the tawayaf tradition began to learn and perform vocal music and dance, the impetus to render these pursuits respectable reached a feverish pitch.

South Asian male audiences still respond openly—with open mouths—to the intense sensuality of Indian art music, but as an intrinsic feature of the music, sensuality, receives very little acknowledgement, except perhaps by foreign scholars. Re-packaging the music as a religious pursuit has helped to cloud the issue. This is not, in any way, a denial of Hindustani music's deeply spiritual nature—just an opinion about the pretentious piousness which has been superimposed on the music.

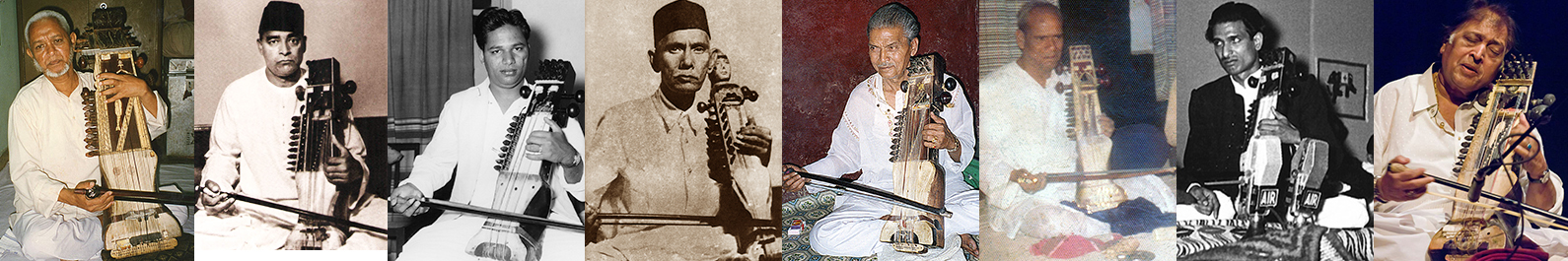

In the nineteenth century sarangi was by far the most common instrument of Indian art music. Many a baiji performed with two sarangi players, one to her left and one to her right, moving with her while she danced, delivering the nagma in stereo. It would have been unusual to find a kotha in any small town of North India that did not have at least one sarangi player (and tabla player!). And sarangi players were commonly the teachers of singers as well as their accompanists. One can see this tradition continuing in my videos of Lakshmi Devi of Banaras: her accompanist Chanda Khan constantly steers her melody and reminds her of song texts. And the sarangi sounds beautiful in unison with the female voice—with a male singer the sarangi has to follow an octave higher than the soloist.

For more on this subject, please see my article "Eros and Shame in North Indian Music" in Music, Dance and the Art of Seduction (2013 Eburon Delft, Delft, Netherlands.

Madhuri Devi

We begin with a performance of over an hour by Madhuri Devi accompanied by the sarangi player Amjad Khan at a kotha in the famous Bow Bazaar neighbourhood of Calcutta, July 1997. This includes a kajri, three dadras, talking and some very exciting dance. As you can here, like in many Indian rooms, the acoustics were excessively "live". Her singing is accompanied by her own seated abinaya.

Firstly a wonderful kajri in Pilu:

Then a dadra:

And another dadra:

Mishra Bhairavi, Pilu dadra and some talk:

Finally Madhuri gets in the mood to do a powerful performance of Kathak dance. Towards the end of the session I had a go on Amjad Khan's sarangi and I play a Bhojpuri kajri from the area around Banaras, one which Madhuri turns out to know, and we sing it together. Great fun! It ends with the entrance of Baby and her sarangi accompanist Ram Kishor Mishra. You can hear their performance later.

Rani Singh

Rani Singh is a prize-winning superb singer of Mirzapuri kajri from Mirzapur, about an hour-and-a-half drive from Banaras. It's a wild place. She put on a beautiful performance accompanied by Maqbul Khan on sarangi, with tabla, harmonium and cymbals all under the watchful gaxe of the madam of the house.This event was in April 1997.

Lakshmi Devi

Our first series of videos are from the mujhra with Lakshmi Bai in April 1994. This film gives great insight into sarangi players' traditional situation. They were not only the accompanists of tawayafs but also their teachers, and often their business managers. In the videos with Lakshmi Devi below, he can be seen coaching her and reminding her of song texts. On Chanda Khan's page, I have presented the entire mujhra in reconstructed order, rather than separating the solo sarangi pieces, which were impressive. Sarangi breaks give the singer a chance to rest. The addition of a tambura playing the drone is not native to the mujhra situation historically, and it can be observed that Lakshmi Devi, used to singing with harmonium, is somewhat disturbed by the drone.

I have removed Chanda Khan's solo sarangi pieces from this page, but you can see them on his dedicated page on this site.

Lakshmi Devi began with a famous bol banao thumri in Mishra Tilang "ankiyan rasile tore Shyam":

This was followed by a dadra:

Now Lakshmi Devi sang a ghazal:

Next was a chaiti, beloved in Springtime:

Then a hori ("karana mose barajori"—the heroine complains about Krishna hassling her) sung by Lakshmi Bai:

Now Lakshmi Devi gets up and dance as well as doing seated abinaya, calculated to thrill (and perhaps embarrass) the men in the audience. Contributions are encouraged and at one point, eaten off the floor:

Next we have a tappa. Here Chand Khan's hotness really shines through:

And then another ghazal:

Then Lakshmi Devi treats us to a dadra in Bhairavi. Interestingly, here Chanda Khan positions Sa as a stopped note (where Re or Dha normally is) on the second string—so as to accommodate Lakshmi Bai's change of pitch:

Baby

Baby arrived in the same room where Madhuri Devi had been singing and dancing, unplanned and unannounced, with her very jolly accompanist Ram Kishor Mishra. So we were surprised to be blessed with a second mujhra.

Baby treated us to a more typical modern mujhra—mainly film songs and filmy light-classical music. Baby had a good voice, and it was an enjoyable performance, enlivened by Ram Kishor Mishra's bubbling enthusiasm. The highpoint was the infamous film song "Tu Chiz Badi Hai Mast Mast".

The entire performance is presented in the following video: