Sarangi lessons

I have been teaching sarangi, vocal music and Hindustani music on a variety of instruments including cello, clarinet, esraj and violin for many years, both at home in my music room and online. I have developed a unique style of teaching that maximises and accelerates my students' progress. Having had many teachers myself, excellent, good, bad and terrible, I have a good idea of how best to teach—especially to students from outside the tradition. Please also see this page about online lessons in sarangi, Hindustani singing and other instruments.

About teaching

It is essential to communicate that ragas are not just scales or series of musical notes—they are intricate pathways for moving between notes. The spaces between the notes are as important as the notes themselves, both in terms of time and of pitch. Much of the emotional impact of this music comes from the many ways of sliding between notes and inflecting the notes, meend, gamak, and kan. Sometimes the power of intertonal space is hard to communicate to Westerners. Students quite quickly get the idea of sliding between notes, but there is a residual fear of intertonal space that inhibits them from making the slides sufficiently audible—with full energy. And silence plays a profound role in good Indian music. The sarangi is such a difficult instrument that even many native players find it difficult to stop playing for a second, to take the bow off the strings and let the resonance of the sympathetic strings suffuse the silence. So they have a bad name for playing too constantly when accompanying vocal music. Just as singers must breathe between phrases, so must instrumentalists.

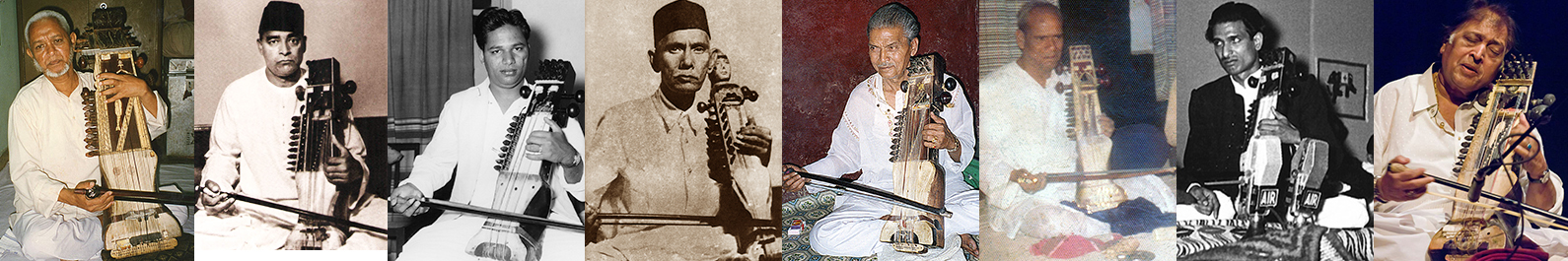

Four of my teachers were especially influential and inspiring of my teaching style:

Pandit Gopal Mishra, my second teacher, inspired me with his profound music and his exuberant and generous personality. He taught in an organised way, bandishes with tans and rhythmic permutations such as tihayis which are often taught to children in the Banaras tradition.

The renowned vocalist Pandit Dilip Chandra Vedi taught me a solid repertoire of essential material in around 20 ragas. In each raga he taught a series of beautifully composed alap sections and one or two songs with intricate tans which captured the raga's essence. This kind of teaching gives the student a confident understanding of what is important in a rag, how its notes are weighted, what the important phrases are, and how to systematically develop a raga in performance. Traditional teaching is largely by osmosis, by imitation, and this works wonderfully with children who grow up in musical families, listening to practice and performance in the home from the moment they are born, absorbing music much as they absorb language. But for students from outside the musical culture—who have limited time to learn, and meagre pre-existing understanding of what the music actually is—this can be a slow and frustrating way to learn. I have seen many non-Asian students who are still flailing about, not knowing what they are doing after several years of learning and practice. Vediji's organised, somewhat academic mode of teaching was a revelation to me, and this way of teaching is important in my style, especially with beginners.

Ustad Abdul Latif Khan taught me in the traditional way after I had already been a professional sarangi player for some years. When I was living in Bhopal, I used to play with him six or seven hours daily, morning and evening. There was very little verbal instruction. Ustad played and I followed, and in this way he imparted many special techniques and subtle nuances, and around 60 ragas. Abdul Latif Khan's quiet and gentle personality was strongly reflected in his music. I also absorbed his understated tone production. I often find myself insisting that a student bow more lightly. Loud playing on the sarangi has a bold harshness with an overpowering ringing from the sympathetic strings`—which makes it difficult to preserve the integrity of elegant musical phrases.

Ustad Mohammed Ali Khan taught me many unique techniques from his uncle, the peerless Ustad Bundu Khan and their extended family as well as hundreds of bandishes from their Delhi gharana. He also shared his esoteric and profound collection of 1001 paltas, note patterns. Bundu Khan and his family were crazy about palta practice. These maps of tonal space are a key to expanding musical consciousness. I often teach paltas. Practising these and other technical exercises together with students is the best route to pushing them forward in terms of speed, coherence and intonation.

For several years I have taught music students from SOAS, University of London and from Goldsmiths University. They normally have five or six months to learn before taking an exam on which they are marked. They are busy with other studies and usually cannot come more than once a week, so it has been a challenge to prepare them to do concise and impressive 20-minute performances on stage at the end of the year. These performances have always been successful, and this process has helped me refine my style of accelerated no-bullshit teaching.