Ustad Bundu Khan, according to many, was the greatest sarangi player who ever lived. He had an immense knowledge of vocal compositions (bandishes) and an unrivalled sensitivity to the nuances of vocal music.

Bundu Khan learned from his grandfather Sangi Khan and his father Ali Jan Khan. However his main teacher was his maternal uncle and father-in-law Mamman Khan, the eldest of Sangi Khan's four sons. Bundu Khan was a court musician in Indore and in Rampur before becoming a staff artist at All India Radio Delhi. He was a friend and informant of the eminent musicologist V N Bhatkhande.

Bundu Khan was a small and quiet man with an opium habit, steadfastly retiring from normal human intercourse. One day before Partition, when Mohammed Ali Jina, the father of Pakistan, was coming to give a speech on Delhi radio, there was naturally a lot of hubbub at the station. People were running here and there preparing. Bundu Khan asked what all the commotion was about. "Haven't you heard? Jina is coming—Mohammed Ali Jina!" Bundu Khan answered calmly "Oh OK—what key does he sing in?".

Sheila Dhar, a very dear friend of mine in Delhi who passed away a few years ago, had many stories to tell about Bundu Khan as he used to visit her father's haweli regularly. At one social gathering he disappeared and was nowhere to be found. He was eventually apprehended, well-hidden in the garden, playing sarangi for the flowers.

A couple of years after partition Bundu Khan emigrated to Pakistan to join other family members there. Sheila Dhar's father arranged and paid for his passage. When he arrived in Pakistan he sent a couple of tans in rag Malkauns as a token of his gratitude.

It is said that at some point in his life he took a vow of silence. He used to go to the market with his sarangi strapped around his neck, and by the tune he played, the sabzi walas knew what vegetables to give him.

One story has it that when Bundu Khan got married, after the ceremony his wife was waiting for him in the appointed room—until the early hours of the morning. She finally went and found him in the bathroom, practising sarangi. "I don't mean to disturb you, Khan Saheb, but you know—we just got married." "What can I do—you can see I'm already married." Whether or not this was the same wife who was the daughter of his teacher Mamman Khan—I don't know.

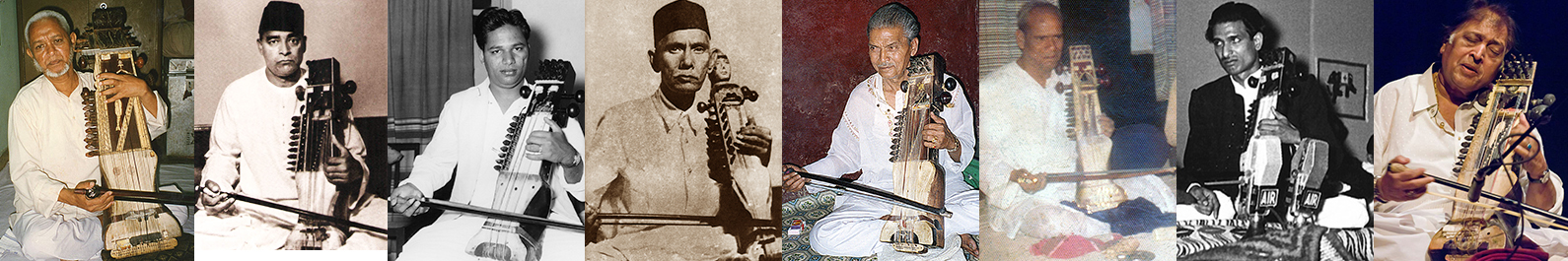

Bundu Khan's music is a rare relic from a forgotten era—before the harmonium wreaked havok on Indian music—when intonation was far from standardised, and the wringing of rasa out of the srutis was an important feature of the music. Bundu Khan was not enamoured of the sarangi's resonance. It is said that over the years he allowed the sympathetic strings on his sarangi to break, one by one, and didn't replace them, prefering the purity of a dryer sound. He also had a bamboo sarangi, as can be seen in one of the pictures of him—dubbed Pinochio by people who shall remain nameless. He usually used a metal jil (the first string of the sarangi).

He produced, I believe, two 78-rpm records including a profound distillation of Darbari and the most intense, mind-blowing and rasa bhare Bhairavi imaginable. A few of his recordings were released on an LP record by EMI Pakistan. Rajesh Bahadur, Sheila Dhar's brother and a student and fan of Bundu Khan's, blessed us with a wonderful AIR National Programme on Bundu Khan in 1977. One of his talks is included as a sound file here, and I shall also transcribe it presently. Other recordings having floated from collector to collector, well-guarded from the rabble. Well here it is—plenty of Bundu Khan to get your teeth into.

I think you need to have an intense love for and some experience of sarangi to appreciate his music. It is not the slick clean stuff which fills the concert halls of modern India. It is real music, sometimes agonising, sometimes relentless, always beautiful.

Bundu Khan had many unique and extraordinary techniques, very unlike any other sarangi player, and I am fortunate to have been able to learn seveal of these from his relative Ustad Mohammed Ali Khan. They involve playing every note with every finger—and especially fast alternations of two fingers in all positions—somewhat akin to sitar techniques. These are detailed in my forthcoming book Sarangi Style in Hindustani Music. Two known students of Bundu Khan were Abdul Majeed Khan (Jajar/Delhi/Bombay) and Sagiruddin Khan (Delhi/Calcutta). Some of Bundu Khan's style can also be heard in Masit Khan's playing, as Masit Khan was a student of Abdul Majeed Khan.

Bundu Khan is known for his solo playing, but he was an inspired accompanist. I have included a recording of him accompanying Ram Krishna Vazebua below. He was also a thinker, and had big plans to publish a twelve volume encyclopedia of Indian music. Sadly he only completed the first volume of the Vivek Darpan, a quirky work full of tans and eccentric pronouncements—his picture from that volume is included in the slideshow above.

The first playlist below is the cream in terms of recording quality—six tracks straight from q source at Radio Pakistan (courtesy of Lowell Lybarger).

Having become acclimatised by listening to these recordings, the novice will be better placed to enjoy the scratchier but no less profound recordings in the second playlist. This is a big gift to the world of sarangi: from Pakistan to India, and from me to you. There's nothing like it.