Nicolas Magriel has been playing the sarangi since 1970. He has spent around twelve years in India studying the sarangi and Hindustani vocal music and also doing research on Indian music. During the 1980s he performed widely in Britain and in Europe both as a soloist and as an accompanist to Hindustani vocal music and kathak dance.

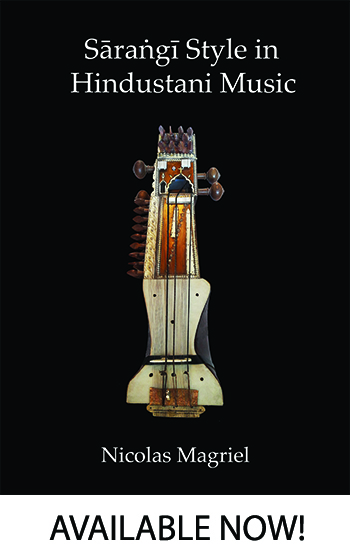

His sarangi can be heard on several film and television soundtracks including The Jewel in the Crown, End of Empire and The Great Gatsby. He has collaborated with pop musicians including George Harrison, Voice of the Beehive, the Suns of Arqa, the Bangles, and Take That. Having completed his PhD on sarangi style at the University of London in 2001, much of the new millenium has been spent on two AHRC-funded research projects, The songs of Khayal, an in-depth two-volume study of Hindustani vocal compositions, and Growing into Music for which he produced seven films on musical enculturation in Hindustani, Rajasthani and Qawwali traditions. His definitive work on all things sarangi, Sarangi Style in Hindustani Music ,was published in 2021, and a South-Asian edition is forthcoming.

Nicolas Magriel: My Musical Journey

Childhood

I was born in New York City. As a toddler I was observed expressing my fascination with music by peeing on revolving phonograph records. My interest in world music was born at the age of five when I fell in love with a Russian balalaika. I used to invent melodies on my balalaika and also fooled around on the piano at home. When I was seven I was sent for piano lessons to an elderly witch who threatened to rap my knuckles with her ruler if I made a mistake. I went home and announced definitively that I didn't like the piano (why didn't I just say "that lady is a witch"?). I fell in love with the banjo when I was nine, hearing it played beside campfires at beach parties on Cape Cod. I went for banjo lessons at a local music school. An old-timer jazz man taught me millions of chord progressions for old standards on the tenor banjo. Something seemed not quite right. After a few months I realized that this guy was never going to teach me frailing or Scruggs-picking because these styles didn't exist on the tenor banjo. The instrument which had won my heart was in fact the 5-string banjo which has a continuously ringing drone string, a premonition of the essential drone of Indian music. Harmony was never my thing. So I started taking lessons and devouring teach-yourself books, learning both "old-timey" banjo styles and the flashier speedy rolls of bluegrass banjo. I started playing the guitar when I was eleven, and used both banjo and guitar to accompany a large body of American folk songs which congregated in my memory. I had a particular affection for union songs although I had no idea what a union was.

My first real guru was the celebrated blind blues singer Reverend Gary Davis who I went to for guitar lessons when I was sixteen. He taught me many of his beautiful ragtime and blues numbers in the two-finger picking style for which he was famous. We sat in a basement in Queens in armchairs which swallowed you up. He had a number ten tin can around the back of his chair which answered to all his bodily needs. Mrs. Davis used to bring us lemonade. After a couple of hours the Reverand would say it was time to feed Miss Gibson—by aiming a five dollar bill for his guitar's sound hole.

As a teenager I started listening a lot to Indian music. The big turn on was the incredible energy of Ali Akbar Khan's sarod playing - particularly the jhala. My first record of Indian vocal music was Rag Madhuvanti by Nazakat and Salamat Ali. Both the music and the cover photograph suggested that these people and their music came from outer space. I'd never heard anything so profoundly and compellingly other-worldly. There was an element of humour in the attraction. I'm reminded of this when confronted with the reactions of unexposed Westerners to the gamaks of Indian vocal music i.e. "is that guy serious?" Years later when I was practising singing on the outskirts of Benares, little children walking past my house on their way home from school used to giggle and imitate the noises I was making.

But the music grows on you. Its meaning for me resided increasingly in the mystical overtones of the peaceful spaces and contemplative tones of alap. I first heard Ram Narain's record The Voice of a Hundred Colours when I was sixteen. The sarangi's appeal lay in the incredible roundness of its tone and, initially, in being apparently even more elusive, abstractly defined, and ethereal than other Indian music. Later I would come to undersand and appreciate the sensuality of the sarangi as well as something of the intellectual richness of Indian music.

Entrance into Indian music

My first instrument with south Asian associations was an Afghani sarinda. The sarinda family of instruments is similar to sarangi in that it is bowed and has sympathetic strings, but it was a distincly different—skull-like—shape, a swollen belly. During my one year at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, I regularly jammed with a group of friends, mixing old-timey, jazz, and Eastern influences and instruments. At this time I was also playing electric guitar, enjoying loudness for its own sake. In 1970 I was in a bad car crash on Route 66 in Oklahoma. The insurance money was enough for a ticket to India, and in the autumn of that year I arrived in Delhi in search of a sarangi teacher. I had just seen my first sarangi in the Golden Temple in Amritsar and had been shocked by its apparent crudeness and by the tangled confusion of strings everywhere.

When I started learning sarangi, I was aware of its reputation for being the most difficult Indian instrument. To some extent the challenge had attracted me. I did not at that time realize that sarangi is famously and infamously the dark sheep of Indian music. I had no idea that from the point of view of many an Indian bystander there was a perplexing incongruity in the phenomenon of a priveleged outsider taking up an instrument which is stigmatized by its association with the courtesan tradition and the low musical and social status of its players.

First teachers

Ustad Sabri Khan, still today one of the most expert sarangi players of India, found me a sarangi and started me off on rag Bhairav with a song in Jhaptal often taught in Muslim sarangi families: Allah hi Allah. I was intrigued and excited by the andulan (broad oscillation of pitch) on the note Dha. Sabri Khan taught me several bandishes in various rags, usually while shaving or attending to some other work. He never taught by demonstration with his own sarangi. I lived in a barsati (a one room flat on the roof) in West Patel Nagar, a dreary middle class area of Delhi, a spine-wrenching auto rickshaw ride to Sabri Khan's place in the medieval Mohallah Nierian area behind Old Delhi's infamous GB Road. I practised like crazy, enjoying the swollen lumps on the back of my fingers, and supplemented my visits to Sabri Khan with vocal lessons at Vinai Chandra's Gandharva Mahavidyalaya. Vinai Chandra eventually suggested that I try contacting Pandit Gopal Mishra who was famous both for his beautiful sarangi playing and for his huge heart and enthusiasm for intoxicants.

Gopal Mishra taught me with great seriousness and warmth. I changed to the Benares fingering of Sarangi, and he taught me 'sumirana kara mana Rama nama ko' in rag Puriya Dhanashri, with a systematic selection of layakari and tihais based on the melody of the bandish. There was a tabla player-cum-interpreter at each lesson. I felt enormous love for Gopal-ji and was very inspired by his music and by his dedication. Every evening, he would go out to a room which was reserved for his practice in another building in Swatantra Bharat Mills' Colony, where he lived. The owner of Swatantra Bharat Mills, Vinay Bharat Ram, was an amateur singer who patronised Gopal Mishra. In the music room he would play with a tabla accompanist for several hours each evening, often staring into my eyes - in awe of his own sublime music. Gopal-ji was a profoundly life-positive musician. He was also a tormented man, and the clash between his own love for life and music and the conservative forces around him eventually claimed his life via the avenue of excessive drinking. He remains very close to my heart.

I couldn't handle the hustle and bustle of living in Delhi. In the autumn of 1971 I shifted to the more romantic and infinitely crazier setting of Banaras (Varanasi). I lived in the country about four miles from Benares and bicycled in to lessons at the home of Gopal Maharaj (yes another Gopal!), a young sarangi player who was very warm and informal but neither an outstanding musician nor a focused teacher. I saw something of the life of music in the kotas of Dalmandi where he was employed teaching girls to sing.

After a few months I moved into the town of Benares and began learning or trying to learn from Gopal-ji's brother Pandit Hanuman Prasad Mishra. In musical terms this was a tremendous mistake. He taught me very little during the three years I lived in Benares: six songs. And the Benares fingering, well-suited to the delicate runs and graces of thumri (light-classical music - the specialty of Benares), is a disadvantage for executing the tans (fast passages) of khyal, the main contemporary form of North Indian vocal art music. I did not make much progress musically but what an experience of Benarsi life! Many years later I understood how fortunate I had been to spend so many days in Hanuman-ji's house partaking in his very formidable, rustic way of life. Joep Bor described him as "the grand old man of the sarangi". His repertoire and style embody all the luscious graces of Benares music. According to Hanuman-ji music is about "swar ko pyaar karna"- loving the notes.

During this period in Benares I also studied with Amiya Bhattacharya, a Bengali gentleman who was a surbahar player and vocalist, a student of Ashik Ali Khan, the Ustad (teacher) of Mustaq Ali Khan, the famous old-style sitarist of Benares. Amiya Babu was a professional teacher. Every student paid ten rupies a lesson, and he taught for the duration of the allotted time for a lesson. This was a welcome antidote to the hours of waiting and running errands for Hanumanji Mishra. Amiya Babu's interest and strength lay in alap, the systematic un-metered exploration of a rag's tonal material. He sang and usually I repeated each phrase singing.

In 1973 I met Durga Prasad Mishra who was known as Pande Maharaj, the brother of the famous dancers Sitara Devi and Alekananda Devi. He was introduced to me as being a sort of musical tantric, and indeed his singing was delivered with such powerful emotion that it seemed to come from some magic realm. He sang for hours on end while I accompanied him, very imperfectly, on the sarangi. Whenever I tried to stop to stretch my legs, he would scream "bajaao, jor se bajaao!" (Play! Play with energy!). Pande Maharaj often cried while he sang. He taught me, often imploringly, to open my heart - in my playing and in my life.

My final teacher during my first five years in India was Mahantji Mahantji Amar Nath Mishra who was the mahant of the Sankat Mochan Temple in Benares, a great guru of wrestling, and an outstanding pakawaj player. He had roughly a thousand wrestling disciples and he was very much in demand by both Dagars and Darbanga dhrupad singers for his sensitive accompaniment. I learned dhrupad singing from him for a few months. I used to walk along the bank of the Ganga every morning with my giant tambura over my shoulder and meet Mahant-ji in a small room in the Tulsi Ghat temple. Mostly we worked on dhrupad in Rag Alaihya Bilaval.

I did it wrong. Either I wasn't satisfied with my teachers or they didn't quench my thirst for the sort of musical experience—transmission—that I expected to have. Anyone will tell you that the best thing is to stick with one teacher through thick and thin. Mutual sympathy and trust need time to develop. I touched a lot of feet, but I wasn't somehow content with touching the same pair of feet forever. On the other hand, I had the opportunity to share in the lives of some extraordinary human beings, to hear a lot of incredible music, and to progress, albeit in a somewhat helter-skelter way, in my sarangi playing.

I settled down in Wales in the end of 1974. I made two trips to India between 1978 and 1980, staying in Delhi for around two years. I studied for this entire period with the veteran singer and musicologist Pandit Dilip Chandra Vedi in Delhi. Vedi-ji had a gift for encapsulating the essential grammar of rags in concise memorised sequences of alap. His barhat was systematic but imaginative. I am deeply grateful to Vedi-ji for teaching me what a rag is: what sorts of restraints one needs to be on the lookout for when trying to come to grips with a new rag. During this period I also studied dhrupad singing with Ustad Fayazuddin Dagar of the younger Dagar Brothers, working microscopically on intonation.

First performances

I started to perform and teach in London in 1981. My first gig was accompanying the world-famous tabla maestro Ustad All Rakha Khan. My next was a tour with the late Latif Ahmed Khan, a great tabla player of the Delhi Gharana. I accompanied many Indian singers and dancers including Ustad Salamat Ali Khan, Ustad Mohammed Sayeed Khan, M.R. Gautam, Shrimati Maya Sen, Gitanjali, Pratap Pawar, and Nahid Siddiqi.

Much of my livlihood came from frequent solo concerts with Live Music Now, an organization founded by Sir Yehudi Menuhin with the aim of bringing art music to the community. This was very enriching work: playing for mentally and physically handicapped children, blind people, and elderly people, as well as in bizarre venues such as the National Garden festival (we played in the hothouse) and a gathering of the Conservative party (we played beside the hors d'oeuvres table) in honour of victims of the Brighton bombing.

During this period I had many solo performances on television, and played for films, theatre, and television productions including Jewel in the Crown, The Razor's Edge, The Last Viceroy, End of Empire, The Bengal Lancer, and The Little Buddha. In films sarangi is usually used for tragic scenes: a village stricken by cholera, a baby bitten by a scorpion, Gandhiji's assassination. But the sarangi can be cheerful also!

I taught Indian singing at Open University summer schools, conducted intensive introductory workshops on Indian singing, and had a few private students. At the same time I was becoming immersed in music technology, reacquainting myself with my electric guitar and producing a novel hybrid music which was characterised by some listeners as "Indo-punk". I tended to play all the instruments myself, not being able to find knowledgable Indian musicians who were excited by rock, or rock musicians who knew rag and tal, to which my new crazy music strictly adhered. I recorded from time to time with pop musicians such as George Harrison, Blancmange, and Voice of the Beehive and performed and recorded with the Sons of Arqa.

While devoting a vast amount of energy to trying to achieve "authenticity" - cultural correctness - in my sarangi playing, I've always needed to counterbalance this often frustrating endeavour with wild activity of some kind or another. I used to go busking from time to time with a marrionette of an Indian dancing girl named Lakshmi whom I created in 1979 in Wales. She's about two feet high and hangs in front of me from a system of poles which is harnessed to my back. Many bells adorn my ankles, clanging while the two of us dance and I play the sarangi. An amplifier hangs from my neck, there's a snake named Shiva who comes out of a basket when I reel in my fishing reel, and there's a transistorised car with a soup can on top that goes around to collect the money. People in Italy loved the car. I used to play a three minute song and then send the car around for twenty minutes. My busking act brings Indian art music to the people. People warm to Indian music and have a laugh; I get fresh air, exercise, sometimes a suntan, meet lots of people, and make lots of money. Lakshmi (see slideshow) flies around in the air at a terrific speed, and we both have lots of fun—a stark contrast to the proprieties of an Indian concert in the diaspora.

Academic life and more teachers

In 1992 I completed an MMus degree in Ethnomusicology at SOAS. My dissertation was a detailed analysis of a performance of khyal by Niaz Ahmed Khan which contrasted emic and etic, insiders' and outsiders' conceptions of the music. The Barhat Tree, a paper derived from this thesis, was published in Asian Music, Volume XXVIII-2, 1997 (The Journal of the Society for Asian Music).

In the autumn of 1993 I studied with the world famous master sarangi player Ustad Sultan Khan. He taught me an impressive body of tans in rag Marva as a vehicle for imbibing his vigorous technique. Sultan Khan had been a good friend for many years. But at this time i made the mistake of getting serious about learning from him. I formally became his disciple which involved a considerable offering of gold (!), and from that time on, he was no longer my friend, and began mistreating me—so sadly my period of being his disciple ended.

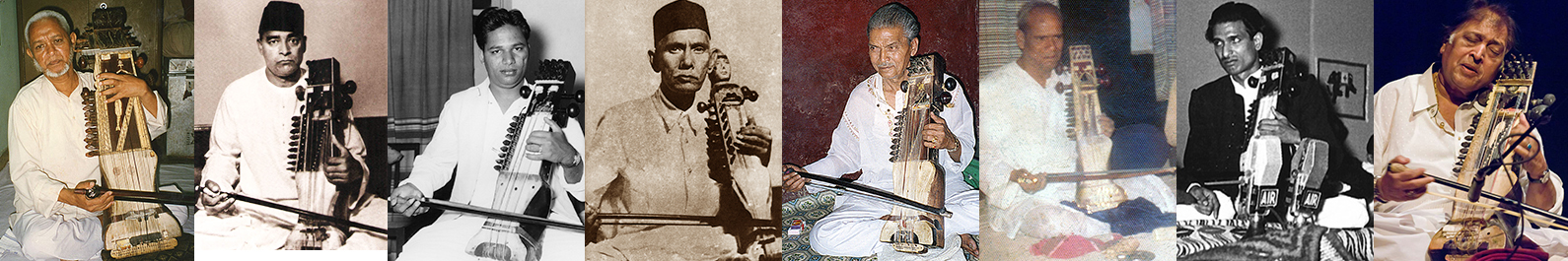

Beginning in 1993, I spent seven years researching and writing my PhD thesis on sarangi style. I spent three of these years in India meeting sarangi players in 28 cities, learning from them, and recording and videoing them playing - usually in their homes. This has resulted in a unique video archive of 450 hours of sarangi playing and sarangi life. My fieldwork began in Benares where I studied with Pandit Baccha Lal Mishra and Zakan Kkan, two fine players especially of purav ang thumri, the sensuous "light classical" music of Benares. I then spent a few months of 1994 with Ustad Ghulam Sabir Qadri, a very wholesome old-timer from Moradabad, now living in Delhi, on the other side of the Yamuna river, who welcomed me warmly and taught me exciting new types of tans as well as the austere old-style jor ang of sarangi.

In the autumn of 1994 I went to Bhopal and became the disciple of Ustad Abdul Latif Khan, one of the greatest living sarangi players (he died in 2002). I lived in Bhopal for several months and returned there periodically during my sarangi travels from one Indian city to another. Abdul Latif Khan is my true Ustad. We harmonized from the first moment we met. When I first went to his house in Bhopal, his 13-year old grandson Sarwar Hussain told me that Ustad was away in Gwalior for two weeks but that he also played, and he invited me to come in and sit down. So I spent two weeks practicing with and learning Ustad's style from this brilliant 13-year-old. In my first few months in Bhopal, Ustad taught me 65 rags and transformed my technique. Generally, when in Bhopal, I spend three hours every morning and every evening at his house, mostly playing. His teaching usually consists of simply playing rags in his uniquely clean and delicate style. He leaves spaces after phrases so that I and/or Sarwar can repeat. He talks very little. I am treated like and feel like a part of his wonderful family. Ustad used to take a walk by the lake in Bhopal every morning around six, and I often accompanied him. He was a real musical father, and my gratitude to him is enormous.

In the beginning of 1996 I began studying singing in Bombay with Batuk Diwanji, a retired public prosecutor with a huge repertoire of khyals and thumris. He had learned Agra gharana-style khayal singing from Khadim Hussain and Vilayat Hussain Khan, but his extraordinary knowledge of and feeling for Banaras thumri came completely from listening to recordings. Batuk-ji is a true gentleman musician. He taught me many beautiful compositions, and treated me with enormous respect and hospitality.

In the summer of 1997 I had the good fortune to meet Ustad Mohammed Ali Khan, a uniquely knowledgeble musician. He played the sursagar, a bizarre king-size sarangi with extra swarmandal (zither-like) strings and chikari (rhythmic drone) strings. The sursagar was invented by his great uncle Mamman Khan. There have only been four sursagars ever made. Mohammed Ali Khan is a descendant of and student of Bundu Khan, widely acknowledged to be the greatest sarangi player in recording history. Mohammed Ali Khan also treated me like a son. He taught no Indian sarangi players, a tragedy as he was the sole possesor of the extraordinary techniques of Mamman Khan, Bundu Khan, and his own grandfather Kale Khan. A pronounced bitterness with regard to the situation of sarangi prevented his disseminating his knowledge except to singers, violinists, and esraj players. He was a superb teacher, bubbling over with the desire to give, and he was very fluent in sargam, the Indian syllables which signify the notes SA, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha and Ni. He taught me all of the extraordinary fingerings of Bundu Khan's style and around a hundred superb bandishes (songs). When I was in Delhi in the summer of 1998, he surprised me by unveiling an old diary in which he'd written 1001 paltas (exercises), some of which he had already taught me. He is rumoured to know 5000 paltas. I cannot express the depth of my gratitude for his kindness in walking out with me in the noonday sun through the alleys of Old Delhi to a photocopy shop and presenting me with a copy of this amazing collection. These are not just exercises. They are beautiful exercises! They are a profound manifestation of the system of mirkand (systematic recombination of tonal material). They carve pathways in the brain - all the possible ways to move from note to note. These paltas constitute the bulk of my morning practice.

After Mohammed Ali Khan's death in 2004, I eventually inherited his sursagar. It is an extremely eccentric instrument with bridges all over the place—in the most unlikely spots, and my feeling is that since the time of its invention by Mamman Khan in the early 20th century, it gradually evolved in an ad hoc and rather improbable direction. It had become endowed with a couple of grotesque bridges of cast aluminium. But after I inherited it, it sat in the corner for some years—as I was afraid to violate this legacy of Mohammed Ali Khan. Finally I renovated it in 2013, bringing it back to life. You can see and hear the suragar in action elsewhere on this site.

In the course of my research on sarangi style I also learned from Ustad Ghulam Sabir Qadri in Delhi and Pandit Baccha Lal Mishra andUstad Zakan Khan in Banaras, all special musicians in their own ways. All three have pages and many videos on this site.

My fieldwork in the '90s resulted in a unique archive of 450 hours of video of sarangi and hundreds of hours of audio, which will all hopefully find its way onto this site. My PhD thesis Sarangi Style in North Indian Music was completed in 2000, and will soon be available as a book (better late than never). Watch these pages.

Research projects

In 2002 I was fortunate to secure a substantial grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Board for a project collecting, transcribing and analysing khayal songs together with the linguist and hindi scholar Lalita du Perron. This involved winters spent in India, mostly Bombay, between 2003 and 2006, mainly in order to consult many singers about song lyrics. During these visits I continued learning vocal music from Batuk Dewanji, and also learned khayal from Ustad Aslam Khan, a highly knowlegable singer of seven gharanas, mainly Harpur and Agra. The style he taught me was largely akin to Agra style, nom tom alap followed by khayal. Aslam Khan lived in a flat in Ruby Mansions, a historical landmark of the Agra gharana, the place where many of its best-known singers had lived when they first came to Bombay—Faiyaz Khan, Vilayat Hussain Khan, Khadim Hussain Khan. It has always been a joy visiting Aslam Khan at Ruby Mansions and getting absorbed into an intensive rendition of some rag or other. My favourite was Dhanashri. The work on khayal finally resulted in The Songs of Khayal, a two-volume work which embodies extremely detailed transcriptions and analysis of 497 khayal songs, all from commercial recordings from the first six decades of the twentieth century—beginning with the first ever recording of khayal, Gauhar Jan's Sur Malhar from 1902. See www.khayalsongs.com.

More trips to India happened yearly from 2009 to 2012—filming classical musicians and also Rajasthani langas and manganiyars for the Growing into Music project, also supported by a generous AHRC grant. Seven of my completed Growing into Musicfilms can be seen both on this website and on www.growingintomusic.co.uk where you can also learn more about the project.

My promiscuity with regard to teachers has had its drawbacks, but it has fostered a healthy eclecticism in my own musical style. Because sarangi is so marginalized in India, no Indian scholar or critic has demonstrated conversance with the differences between the main distinct styles of sarangi playing. Many do not even know that the sarangi's strings are stopped with the back of the left hand fingers. I feel privileged to have been able to do a thorough study of sarangi style, and to be able to describe the specialities of the various existing styles and demonstrate them via my own playing. See A Life with Sarangi, a film by Rolf Killius (alsoavailable in the "Nicolas" page of the Sarangi Archives on this site).

Since the autumn of 2014 I have been constructing this website while editing my PhD thesis. A greatly augmented version was finally published in 2021 as Sarangi Style in Hindustani Music. This website has been gruellingly reconstructed in 2024 in order to meet the demands created by advances in internet technology.